|

| The Real Face of Marquis de Lafayette - Life Mask Reconstruction (yarbs.net) |

|

| "Franklin had written to Washington asking him to take the young man on, in hopes of securing an increase in French aid to the American war effort. The two men bonded almost immediately, forming a relationship closely resembling that of father and son. The fatherless young French officer, and the father of his country who went to his grave, childless."-June 13, 1777 An Indispensable Man – Today in History |

|

| Library of Congress: The Marquis de Lafayette was the last surviving general of the Revolutionary War. He is shown here, with his commander in chief, Gen. George Washington, at Valley Forge, 1777-78. |

|

| Paris, 1815 |

In 1824 Lafayette accepted an official invitation from President James Monroe and Congress to visit the U.S. Not only did the invitation give the U.S. the opportunity to express its gratitude to the only surviving major general of the American Revolution, it also enabled Lafayette to restore his political clout and fortune. Defeated in the February 1824 election to the Chamber of Deputies, discredited for his role in the Carbonari conspiracies, and finding himself in financial straits, Lafayette hoped to serve the liberal cause in France. He publicized the trip's political significance by sending reports to the French press through his secretary, Auguste Levasseur. If the trip was advantageous to Lafayette, it was also a boon to fledgling American industries. Printers, glassblowers, and other craftsmen vied with each other to produce souvenirs – from snuff boxes, ribbons, flasks, bottles, and bandanas to engravings, songs, and plays. Levasseur left the only eyewitness report of the entire tour. Although at times he could not keep dates straight, his two-volume work, published in France in 1828 and in two American translations in 1829, remains the most accurate account of a visit that unified the disparate twenty-four states of America.

Lafayette arrived at Staten Island on August 15. For over a year, his tour provoked demonstrations of an enthusiasm without precedent in American history. After his reception in New York, he traveled across New England to Boston, and then southward through Philadelphia and Baltimore, making leisurely stays everywhere. After a long stay in Washington, D.C., he joined the October anniversary celebrations at Yorktown. He visited Monticello from November 4-15 and then returned to Washington for official events and receptions during most of the winter. At the end of February, he went southward through the coastal states and to New Orleans. He made his way to St. Louis before traveling back to the east on a route that passed through Nashville, Louisville, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Buffalo, and dozens of small towns. He visited Braddock's Field, Lake Erie, Niagara Falls, and other American battlefields. He returned to Boston for the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill. He visited New York City four times on this trip, and before he left, he enjoyed a final visit with Jefferson from August 18-21. Lafayette attended more receptions in Washington before his departure for France on September 8, 1825, on the new frigate "Brandywine", named in honor of his first battle.

|

| When asked for his reaction to the murder of Hamilton by Aaron Burr, Lafayette replied. “Hamilton was to me, my dear Sir, more than friend, he was a brother.” |

Although the tour was orchestrated as a public event and generated optimism about the consequences of legal and political equality in a democratic society, Lafayette also took time to make private visits with old friends like John Adams, Albert Gallatin, and Thomas Jefferson. Lafayette informed Jefferson of his plans to travel south and Jefferson replied that "our little village of Charlottesville insists also on recieving you." Lafayette had to postpone his arrival at Monticello for several weeks, and when he finally arrived at the county line, Jefferson sent him a letter of welcome through his grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph. On November 4, Lafayette entered Albemarle County. After a brief ceremony and a lunch at Mrs. Boyd's tavern, he set out for Monticello at noon in a landau drawn by four gray horses. A long procession accompanied him. Amidst a number of spectators, a bugle announced his approach, and two lines, one of ordinary citizens and one of cavalrymen, formed on two sides of the ellipse on the east front of the house.

Lafayette's Visit to Monticello (1824) | Thomas Jefferson's Monticello

Thomas Jefferson Randolph: "His escort — one hundred and twenty mounted men — formed on one side in a semicircle extending from the carriage to the house. A crowd of about two hundred men, who were drawn together by curiosity to witness the meeting of these two venerable men, formed themselves in a semicircle on the opposite side. As Lafayette descended from the carriage, Jefferson descended the steps of the portico. The scene which followed was touching. Jefferson was feeble and tottering with age — Lafayette permanently lamed and broken in health by his long confinement in the dungeon of Olmutz. As they approached each other, their uncertain gait quickened itself into a shuffling run, and exclaiming, "Ah, Jefferson!" "Ah, Lafayette!" they burst into tears as they fell into each other's arms. Among the four hundred men witnessing the scene there was not a dry eye — no sound save an occasional suppressed sob. The two old men entered the house as the crowd dispersed in profound silence.

Jane Blair Cary Smith: "On a golden November day we watched for the coming guests on the south western terrace. At length, in an open space at the foot of the mountain we discerned a train of several carriages, followed by 40 or 50 men on horseback. Then all was hurry and expectation! A few favored guests were assembled — among whom were Mr. and Mrs. Madison, and about a dozen young lady relatives, some of whom were beautiful enough to grace any reception. All were assembled in the portico, a stone structure with massive doric columns on the N.W. front of the house, Mr. Jefferson, Mrs. Randolph, Mr. and Mrs. Madison being the centre of the group. We lost sight of the cortege; as it wound around the base of the mountain, but at length through the pendant branches of the willows, we saw them with all the military show of gay scarfs and prancing horses, whose glittering accoutrements flashed in the sunshine as they formed in line on the edge of the lawn. Who can tell the excitement of that hour to a country rustic, who had seen nothing! Emotions so intense cd. not be experienced in our day, when girls of 14 or 15 are veterans and can stand the charge in a battle of sensations unmoved — At length, the first carriage reached the lawn and drew up; a crowd of gentlemen dismounted in eager haste and the Guest of the Nation was handed out: simultaneously Mr. Jefferson had walked to the edge of the lawn hurriedly and bareheaded to meet his guest. They embraced and kissed each other on the cheek in European fashion: — all was so still that we heard the words distinctly — "My dear Jefferson! — My dear Lafayette!"

The whole was a scene for an artist — a grand historic picture should have commemorated this meeting — on this mountaintop — the long chain of wavy outline, where the Blue Ridge met the horizon — the expanse of level country stretching away — away — until it seemed an ocean in the distance, — a high rugged peak in the front view — all beautified by the soft golden veil of Indian summer — the mystery and glory of our Autumn! At this moment few, if any had leisure to do aught but feel these influences; for all eyes were rivetted upon the principal figures of the [pair] — the distinguished soldier and the great statesman. The General was led up the steps by Mr. Jefferson, and introduced to Mrs. Randolph, whom he remembered as a school-girl at the Convent of St. Cyr, and then as the mistress of her father's house in Paris: he kissed her hands repeatedly and spoke many kind words as she received him with a grace peculiarly her own — a stately, elegant woman she was on all occasions, always self[-]possessed, though shrinking with painful timidity from notoriety. She then introduced her daughters and nieces, and among those white robed girls were some of the fairest the General had seen in all his long wanderings: — they crowded eagerly to touch the hand that had wielded a sword in our great Revolution. I had been accustomed to see MR. JEFFERSON — MR. MADISON — and MR. MONROE, but this French hero was a [spell?] to my inexperience: after various and long sittings in the parlor I discovered that a great soldier is not always a great man in the broadest sense. Fayette was good and noble natured and possessed excellent sense and tact, but intellectually he did not rise above mediocrity; and Mr. George La Fayette was a very commonplace sort of Frenchman." .......

Lafayette's memoirs include a description of the visit: "Mr. Jefferson received me with a strong emotion. I found him much aged, without doubt, after a separation of thirty-five years, but bearing marvelously well under his eighty one years of age, in full possession of all the vigor of his mind and heart which he has consecrated to the building of a good and fine university.... To-day [November 8] we visited this beautiful institution which occupies the honored old age of our illustrious friend. His daughter Mrs. Randolph lives with him; he is surrounded by a large family and his house is admirably located. We attended a public banquet in Charlottesville, MM. Jefferson and Madison were with us; the answer which Mr. Jefferson had read to the toast in his honor brought tears to everybody's eyes." It was in this toast that Jefferson summarized Lafayette's contributions to the American Revolution...

Thomas Jefferson Randolph: At a dinner given to Lafayette in Charlottesville, besides the "Nation's Guest," there were present Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe. To the toast: "Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence — alike identified with the Cause of Liberty," Jefferson responded in a few written remarks, which were read by Mr. Southall. We find in the following extract from them a graceful and heartfelt tribute to his well-loved friend:

"I joy, my friends, in your joy, inspired by the visit of this our ancient and distinguished leader and benefactor. His deeds in the war of independence you have heard and read. They are known to you, and embalmed in your memories and in the pages of faithful history. His deeds in the peace which followed that war, are perhaps not known to you; but I can attest them. When I was stationed in his country, for the purpose of cementing its friendship with ours and of advancing our mutual interests, this friend of both was my most powerful auxiliary and advocate. He made our cause his own, as in truth it was that of his native country also. His influence and connections there were great. All doors of all departments were open to him at all times; to me only formally and at appointed times. In truth I only held the nail, he drove it. Honor him, then, as your benefactor in peace as well as in war."

Israel Jefferson, a slave: "In those times I minded but little concerning the conversations which took place between Mr. Jefferson and his visitors. But I well recollect a conversation he had with the great and good Lafayette, when he visited this country in 1824 or 1825, as it was of personal interest to me and mine. General Lafayette and his son George Washington, remained with Mr. Jefferson six weeks, and almost every day I took them out to a drive.

On the occasion I am now about to speak of, Gen. Lafayette and George were seated in the carriage with him. The conversation turned upon the condition of the colored people — the slaves. Lafayette spoke indifferently; sometimes I could scarcely understand him. But on this occasion my ears were eagerly taking in every sound that proceeded from the venerable patriot's mouth.

Lafayette remarked that he thought that the slaves ought to be free; that no man could rightly hold ownership in his brother man; that he gave his best services to and spent his money in behalf of the Americans freely because he felt that they were fighting for a great and noble principle — the freedom of mankind; that instead of all being free a portion were held in bondage (which seemed to grieve his noble heart); that it would be mutually beneficial to masters and slaves if the latter were educated, and so on. Mr. Jefferson replied that he thought the time would come when the slaves would be free, but did not indicate when or in what manner they would get their freedom. He seemed to think that the time had not then arrived. To the latter proposition of Gen. Lafayette, Mr. Jefferson in part assented. He was in favor of teaching the slaves to learn to read print; that to teach them to write would enable them to forge papers, when they could no longer be kept in subjugation.

This conversation was very gratifying to me, and I treasured it up in my heart." ......

27 Reasons Why We Should Honor General Lafayette

"5. Under General Nathanael Greene's command, he was sent to lead a reconnaissance mission. He ran into Hessians who outnumbered him and his men and drove them reeling into defeat at Gloucester, New Jersey, November of 1777.

7. He served with distinction at Valley Forge during the terrible winter of 1777-1778 when General Washington sent him on a reconnaissance mission to Barren Hill (now Lafayette Hill). It was here that the young lion and his 2200-man detachment on May 20, 1778 were completely surrounded by British Generals Grant, Grey, Howe, and Clinton, and Hessian General von Knyphausen with 16,000 of their crack British and Hessian troops. With the coolness of a superbowl quarterback, Lafayette--outnumbered 8-to-1--outfoxed the enemy and returned to Valley Forge with a minimum of casualties. His mission accomplished, the youthful general had pulled off one of the most astonishing escapes in the annals of military history. The enemy was stunned by their failure to capture him with the most powerful army on Earth. At Barren Hill Lafayette was the first Continental officer to trust, test and prove the value of General Baron von Steuben's masterful training and discipline of Washington's troops at Valley Forge by virtue of this stunning escape.

9. His generosity to his American troops--many of them Pennsylvanians-- was legendary. He spent $200,000 of his own money to pay for their much-needed items such as clothing and weapons at a time when the American economy was on the verge of collapse.

11. Realizing Washington's dangerous military dilemma by late 1778 and still awaiting the military and financial help promised the Americans by his country, he returned to France and argued for a speedy delivery. He arrived in Paris and Versailles January 1779. Using his diplomatic skills, he made strong appeals to three influential ministers: Vergennes, Maurepas, and Montbarey and King Louis XVI himself to send Washington a French Expeditionary Force complete with all supplies as soon as possible. The king sent him back to General Washington at Morristown, New Jersey on March 1780 with a secret message: the Expeditionary Force was on its way. Thousands of crack French troops, marines, and battleships with massive aid arrived at Newport, Rhode Island July 1780. All historians agree that without this help, Washington would have lost the War for Independence. Washington and Franklin credit Lafayette with the effort behind the delivery of these desperately needed supplies.

12. Because of his proven military ingenuity, Lafayette was chosen by Washington in 1781 to command American troops for the purpose of preventing British General Cornwallis from ravaging the state of Virginia and driving a strategic wedge between the American forces already deployed in the South and the North. An outnumbered Lafayette, with the valuable aid of Generals Anthony Wayne and John Peter Muhlenberg and their Pennsylvanians, cleverly used guerrilla tactics to harass and corner the British commander and pin him down at Yorktown until he was defeated on October 19, 1781 by French and American armies under General Washington's supreme command. Lafayette had become one of the key players and a hero of Yorktown. Washington's patient yet brilliant military strategy paid off; he won the War of Independence.

15. President James Monroe invited him to America as the nation's guest of honor from August 1824 until September 1825. During those thirteen months he visited every state in the Union--all twenty-four of them. Americans treated him as though he were a superstar everywhere he went. He took Philadelphia by storm from September 8 until October 6, 1824. Inside the State House where the Declaration and the Constitution were signed forty-eight years ago, he gave a speech that became one of the most important in American history.

Unfortunately, however, many of our present generation of young Americans have lost sight and interest in the foundations or the historical significance of American Revolutionary War history. We therefore need to remind them and future generations of this millennium that America for many good reasons is still the leader of the free world and that the freedoms we cherish today resulted from the sacrifices of our founding fathers and our foreign volunteers like Lafayette.".......

Lafayette's Visit to the United States, 1824-1825 (schillerinstitute.com)

|

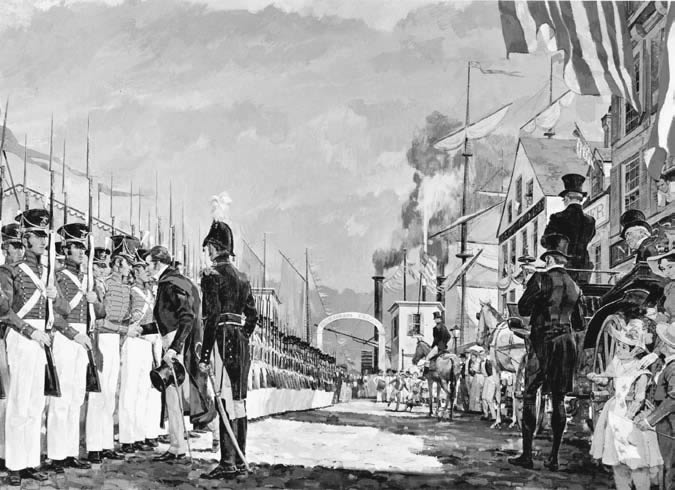

| Lafayette greets the troops of the 2nd Battalion, 11th New York Artillery, in New York City, July 14, 1825. This unit later adopted the title “National Guard” in honor of Lafayette’s Garde National de Paris. |

No comments:

Post a Comment