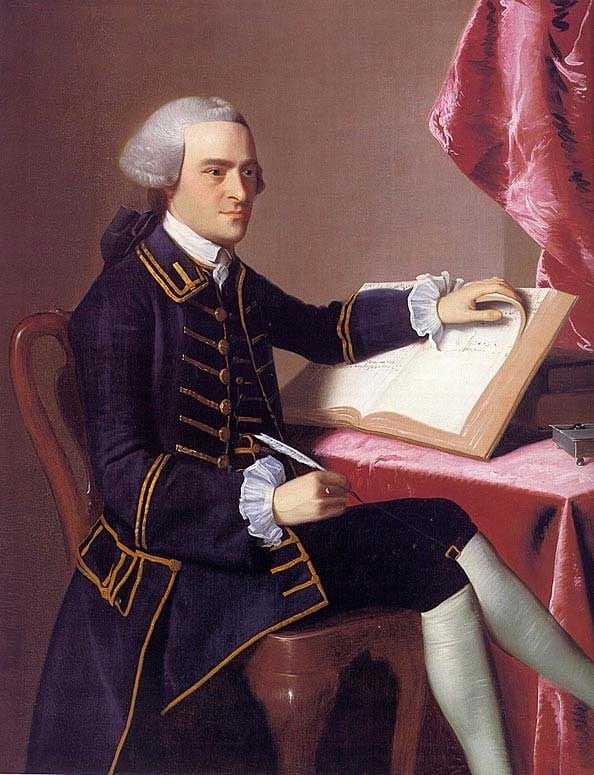

“Resistance to tyranny becomes the Christian and social duty of each individual. … Continue steadfast and, with a proper sense of your dependence on God, nobly defend those Rights which Heaven gave, and no man ought to take from us.”--John Hancock, First Signer of the Declaration of Independence, Seventh "President of the United States in Congress Assembled" under the Articles of Confederation, Smuggler and Sam Adams' partner in American Liberty

"The Glorious Cause was to a large degree a young man’s cause. The commander in chief of the army, George Washington, was himself only forty-three. John Hancock, the President of the Continental Congress, was thirty-nine, John Adams, forty, Thomas Jefferson, thirty-two, younger even than the young Rhode Island general. In such times many were being cast in roles seemingly beyond their experience or capacities...“The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth,” Paine had written. “Everything that is right or reasonable pleads for separation.” In fact, the Americans of 1776 enjoyed a higher standard of living than any people in the world. Their material wealth was considerably less than it would become in time, still it was a great deal more than others had elsewhere. How people with so much, living on their own land, would ever choose to rebel against the ruler God had put over them and thereby bring down such devastation upon themselves was for the invaders incomprehensible. A British ship’s surgeon who used the privileges of his profession to visit some of the rebel camps, described roads crowded with carts and wagons hauling mostly provisions, but also, he noted, inordinate quantities of rum — “for without New England rum, a New England army could not be kept together.” The rebels, he calculated, were consuming a bottle a day per man. The town, although it had “suffered greatly,” was not in as bad shape as [Gen. Sullivan] had expected, he wrote to John Hancock, “and I have a particular pleasure in being able to inform you, sir, that your house has received no damage worth mentioning.” Other fine houses had been much abused by the British, windows broken, furnishings smashed or stolen, books destroyed. But at Hancock’s Beacon Hill mansion all was in order, as General Sullivan also attested, and there was a certain irony in this, since the house had been occupied and maintained by the belligerent General James Grant, who had wanted to lay waste to every town on the New England coast. “Though I believe,” wrote Sullivan, “the brave general had made free with some of the articles in the [wine] cellar.”"--quotes from 1776"

Some smugglers are good people who differ little from the founders of our nation such as John Hancock, whose flamboyant signature graces our Declaration of Independence. The British had levied confiscatory taxes on molasses, and John Hancock smuggled an estimated 1.5 million gallons a year. His smuggling practices financed much of the resistance to British authority -- so much so that the joke of the time was that "Sam Adams writes the letters (to newspapers) and John Hancock pays the postage."Jasmin K. Williams tells us more:

Hancock was in the business of importing and exporting goods. Britain's proposed Stamp Act would greatly restrict trade activities. Hancock became one of the most vehement protesters of Britain's taxation of colonial trade goods after his ship, Liberty, was seized for transporting contraband. As it became increasingly difficult to make a profit in trade due to Britain's unfair tax practices, Hancock began smuggling goods such as glass, lead, paper and tea into the colonies. In fact, it was Hancock's boycott of British tea that led to the famous Boston Tea Party. Hancock's merchant business and smuggling financed much of Boston's resistance movement.

The private financier became publicly critical. On March 5, 1774, Hancock gave a speech in which he condemned British rule.

Hancock's rebellious activities didn't go unnoticed by Britain, There was a bounty on his head and that of Tea Party organizer Samuel Adams. As it became clear that Britain was not going to give up its hold on the colonies without a fight, Hancock and Adams left Boston. The pair hid out in Lexington. During his famous midnight ride, Paul Revere roused the two, warning them that the British were coming and would be there at dawn for the Battle of Lexington and Concord.

The two escaped just at the British broke into the house where they had been hiding. British Gen. Thomas Gage demanded that the pair be arrested for treason. After the battle, a pardon was issued to anyone who swore loyalty to the British crown -except Hancock and Adams.

|

"Some boast of being friends to government; I am a friend to righteous government, to a government founded upon the principles of reason and justice; but I glory in publicly avowing my eternal enmity to tyranny. Is the present system... a righteous government – or is it tyranny? ...Surely you never will tamely suffer this country to be a den of thieves. Remember, my friends, from whom you sprang. Let not a meanness of spirit, unknown to those whom you boast of as your fathers, excite a thought to the dishonor of your mothers I conjure you, by all that is dear, by all that is honorable, by all that is sacred, not only that ye pray, but that ye act; that, if necessary, ye fight, and even die, for the prosperity of our Jerusalem. Break in sunder, with noble disdain, the bonds with which the Philistines have bound you. Suffer not yourselves to be betrayed, by the soft arts of luxury and effeminacy, into the pit digged for your destruction. Despise the glare of wealth. That people who pay greater respect to a wealthy villain than to an honest, upright man in poverty, almost deserve to be enslaved; they plainly show that wealth, however it may be acquired, is, in their esteem, to be preferred to virtue." --John Hancock, Boston Massacre Speech, March 5, 1774 |

Russell Yos: John Hancock Facts, Biography, Signature - The History Junkie:

John Hancock was born in Braintree, Massachusetts to a minister. As a boy, he was a casual acquaintance with the young John Adams. His father passed away in 1744 and he moved to the home of his Uncle Thomas Hancock. Thomas was a wealthy merchant who imported manufactured goods to Britain and exported goods such as rum, fish, and whale oil. Thomas would be an influential figure in his nephew’s life. Hancock went to the Boston Latin School and eventually Harvard College. After graduating he rejoined his uncle Thomas and began to learn more about his business. Thomas had relationships with every royal governor in Massachusetts and was well-connected throughout. John learned much from him during this time and Thomas prepared him to take over his business when he was gone.

John moved to England from 1760-1761. Here he met and built relationships with other suppliers, customers, and other businessmen. He soon went back to Boston and gradually started to take over his uncle’s business since Thomas’ health was failing. When Thomas died John inherited everything, making him the wealthiest man in New England. This wealth would aid the rebellion.

John Hancock married Dorothy Quincy in 1775. The two of them had two children, but neither survived to adulthood. She was known as a great hostess.

|

| "The more people who own little businesses of their own, the safer our country will be, and the better off its cities and towns; for the people who have a stake in their country and their community are its best citizens." |

John Hancock’s Pre-War Activities

John Hancock is usually noted for his resistance to the Stamp Act, Townshend Acts, and Intolerable Acts, but what many misses is why he opposed them. Men like Samuel Adams and James Otis opposed the taxes on constitutional grounds however Hancock opposed them on economic grounds. He did not believe that they were good economic policies and that the tax on specific goods would actually hurt the colonial economy. One can be sure that he was protecting his own interests since he was a wealthy merchant, but he was a believer in the free market and did not like government involvement, whether it be British or colonial, within it.

One cannot speak of John Hancock without also speaking of Samuel Adams. The fate of these men was connected. Without Samuel Adams, Hancock would have never gained much influence in the political realm and without John Hancock’s inherited wealth, Adams would have never ascended. Although they were connected the two could not be more different. Samuel Adams was a Puritan who lived modestly and did not fuss over possessions. Hancock lived extravagantly and enjoyed the life of luxury.

Battles of Lexington and Concord

Shortly before the battles of Lexington and Concord Hancock was unanimously elected as President of the Second Continental Congress. He was a solid choice for this position for a couple of reasons. He was wealthy so many of the moderates could be influenced by him. His close ties to many radicals meant that the radicals in the Continental Congress liked him. He also had experience mediating for legislative bodies. This is primarily what his responsibilities were. Outside of dealing with paperwork his main job was mediating the debate on the floor.

John Hancock during the Second Continental Congress

Tradition suggests that John Hancock believed that he was to be nominated by John Adams to be commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. This would have been unwise since Adams was a Massachusetts man and Hancock did not have the military experience necessary to lead an army. However, Adams himself said later in life that Hancock was disappointed when he nominated George Washington instead of him. If that were the case, then Hancock did an exceptional job hiding it. He supported Washington with word and deed.

It is said that when the Declaration of Independence was signed John Hancock wrote his name large so King George could read it without his spectacles. That story is most likely not true and did not surface until later. However, that story has become folklore and has coined the phrase “put your John Hancock on this” meaning “put your signature on this.” What really happened is that John Hancock was the first and only to sign the treasonous document before anyone else. The document was then sent to George Washington who read it in front of the troops. There was actually no ceremonial signing on July 4, 1776. Rather, the delegates were coming in and out all summer to sign the document. Congress approved the wording of the document on July 4, but it was not signed by all the delegates until August 2 or after.

John Hancock after the American Revolutionary War

Hancock was elected as governor of Massachusetts in 1780 and was easily re-elected for a second term. He took a hands-off approach to the government and did not stick his neck out on any controversial issues. He surprised many by resigning in 1785, citing his failing health. John Hancock, although very ill, helped ratify the constitution. He gave a stirring speech which was the first time that he and fellow patriot Samuel Adams agreed in a while, which probably tilted favor to the ratification of the Constitution. The ratification passed by a narrow margin, but it did pass, largely due to Hancock and Adams’ efforts.

The Death of John Hancock John Hancock died on October 8, 1793, with his wife by his side. On the day of his death, Samuel Adams declared it to be a state holiday. His funeral was lavish and expensive. It was most likely the most expensive funeral Massachusetts had ever seen at that time.".......

The Sons of Liberty (constitutionfacts.com)

Speeches by John Hancock (john-hancock-heritage.com)

|

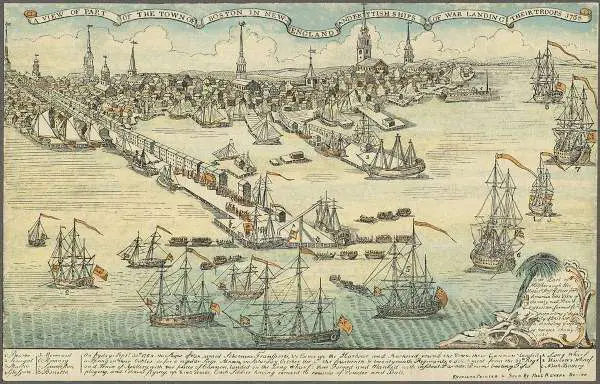

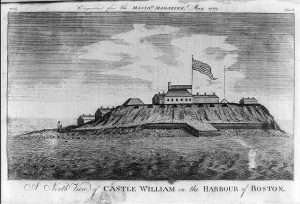

| Liberty Forever! Patriot's Day UPDATE: Paul Revere recounts his Midnight Counter-Intelligence Ride Patriots Day, April 19th - Mr. Paul Revere Explains The Battle of Lexington and Concord in His Own Words - The Last Refuge "In the Winter, towards the Spring, we frequently took Turns, two and two, to Watch the Soldiers, By patrolling the Streets all night. The Saturday Night preceding the 19th of April, about 12 o'Clock at Night, the Boats belonging to the Transports were all launched, & carried under the Sterns of the Men of War. (They had been previously hauled up & repaired). We likewise found that the Grenadiers and light Infantry were all taken off duty. From these movements, we expected something serious was to be transacted. On Tuesday evening, the 18th, it was observed, that a number of Soldiers were marching towards the bottom of the Common. About 10 o’Clock, Dr. Warren Sent in great haste for me, and begged that I would immediately Set off for Lexington, where Messrs. Hancock & Adams were, and acquaint them of the Movement, and that it was thought they were the objects. When I got to Dr. Warren’s house, I found he had sent an express by land to Lexington – a Mr. Wm. Dawes. The Sunday before, by desire of Dr. Warren, I had been to Lexington, to Mess. Hancock and Adams, who were at the Rev. Mr. Clark’s. I returned at Night thro Charlestown; there I agreed with a Col. Conant, & some other Gentlemen, in Charleston, that if the British went out by Water, we would shew two Lanterns in the North Church Steeple; if by Land, one, as a Signal; for we were apprehensive it would be difficult to Cross the Charles River, or get over Boston neck."....... It's good to hear of an American Intelligence Community that's pro-Liberty for a change--even if it is two and a half-centuries old. |

No comments:

Post a Comment