Introduction:

"Jefferson’s letter to John B. Colvin is one of the most important statements by a president about what the English philosopher John Locke called the prerogative power. According to Locke, the prerogative power is the power to act “without the prescription of the law, and sometimes even against it,” for the public good. Jefferson wrote his letter in response to Colvin’s question whether sometimes officers in high trust had to act beyond the law. Colvin had also notified Jefferson that he was writing the memoirs for General James Wilkinson who had violated the law in order to put down the Burr Conspiracy, so it is likely that Jefferson knew his words would find their way to print. The Conspiracy was and remains somewhat hazy with respect to all of the facts, but it turned on some scheme by Aaron Burr to either incite an insurrection among enslaved persons in Louisiana and or start a new republic in present day Texas. Burr was captured and tried for treason. Somewhere along the way, Burr was denied key rights of the accused. Because the Burr Conspiracy was a controversial event in Jefferson’s second term, it is also likely that Jefferson chose his words with great care.

Jefferson’s answer begins with several examples that are meant to lead to an easy answer: when necessary for self-preservation, the unwritten law of survival must be paramount to the written law. But Jefferson complicates his answer with a “hypothetical,” which no longer seems to be about self-preservation. Having thus prepared the way with these examples, Jefferson answers Colvin’s question about Wilkinson and Burr. Importantly, Jefferson never asserts a constitutional basis for the prerogative. Rather, he requires that the officer come clean and accept judgment by Congress or the people after the fact." .......

Thomas Jefferson to John B. Colvin, 20 September 1810--Founders Online:

"Your favor of the 14th has been duly received, and I have to thank you for the many obliging things respecting myself which are said in it. If I have left in the breasts of my fellow citizens a sentiment of satisfaction with my conduct in the transaction of their business it will soften the pillow of my repose thro’ the residue of life.

The question you propose, whether circumstances do not sometimes occur which make it a duty in officers of high trust to assume authorities beyond the law, is easy of solution in principle, but sometimes embarrassing in practice. A strict observance of the written laws is doubtless one of the high duties of a good citizen: but it is not the highest. The laws of necessity, of self-preservation, of saving our country when in danger, are of higher obligation. To lose our country by a scrupulous adherence to written law, would be to lose the law itself, with life, liberty, property and all those who are enjoying them with us; thus absurdly sacrificing the end to the means. When, in the battle of Germantown, General Washington’s army was annoyed from Chew’s house, he did not hesitate to plant his cannon against it, altho’ the property of a citizen. When he besieged Yorktown, he levelled the suburbs, feeling that the laws of property must be postponed to the safety of the nation. While that army was before Yorktown, the Governor of Virginia took horses, carriages, provisions and even men, by force, to enable that army to stay together till it could master the public enemy; and he was justified. A ship at sea in distress for provisions meets another having abundance, yet refusing a supply; the law of self-preservation authorizes the distressed to take a supply by force. In all these cases the unwritten laws of necessity, of self-preservation, and of the public safety control the written laws of meum and tuum [mine and thine, that is, of private property].

After the affair of the Chesapeake, we thought war a very possible result. Our magazines were illy provided with some necessary articles, nor had any appropriations been made for their purchase. We ventured however to provide them and to place our country in safety, and stating the case to Congress, they sanctioned the act.

To proceed to the conspiracy of Burr, and particularly to General Wilkinson’s situation in New Orleans. In judging this case we are bound to consider the state of the information, correct and incorrect, which he then possessed. He expected Burr and his band from above, a British fleet from below, and he knew there was a formidable conspiracy within the city. Under these circumstances, was he justifiable in seizing notorious conspirators? On this there can be but two opinions; one, of the guilty and their accomplices; the other, that of all honest men.

In sending them to the seat of government when the written law gave them a right to trial in the territory? The danger of their rescue, of their continuing their machinations, the tardiness and weakness of the law, apathy of the judges, active patronage of the whole tribe of lawyers, unknown disposition of the juries, an hourly expectation of the enemy, salvation of the city, and of the Union itself, which would have been convulsed to its center, had that conspiracy succeeded, all these constituted a law of necessity and self-preservation, and rendered the salus populi [the welfare of the people] supreme over the written law.

The officer who is called to act on this superior ground, does indeed risk himself on the justice of the controlling powers of the Constitution, and his station makes it his duty to incur the risk. But those controlling powers, and his fellow citizens generally, are bound to judge according to the circumstances under which he acted. They are not to transfer the information of this place or moment to the time and place of his action: but to put themselves into his situation. We knew here that there never was danger of a British fleet from below, and that Burr’s band was crushed before it reached the Mississippi. But Gen. Wilkinson’s information was very different, and he could act on no other.

From these examples and principles, you may see what I think on the question proposed. They do not go to the case of persons charged with petty duties, where consequences are trifling, and time allowed for a legal course, nor to authorize them to take such cases out of the written law. In these the example of overleaping the law is of greater evil than a strict adherence to its imperfect provisions. It is incumbent on those only who accept of great charges, to risk themselves on great occasions, when the safety of the nation, or some of its very high interests are at stake. An officer is bound to obey orders: yet he would be a bad one who should do it in cases for which they were not intended, and which involved the most important consequences. The line of discrimination between cases may be difficult; but the good officer is bound to draw it at his own peril, and throw himself on the justice of his country and the rectitude of his motives.

I have indulged freer views on this question on your assurances that they are for your own eye only, and that they will not get into the hands of newswriters. I met their scurrilities without concern while in pursuit of the great interests with which I was charged, but in my present retirement no duty forbids my wish for quiet.

Accept the assurances of my esteem and respect,

TH. JEFFERSON" .......

Charlie often quoted from this:

|

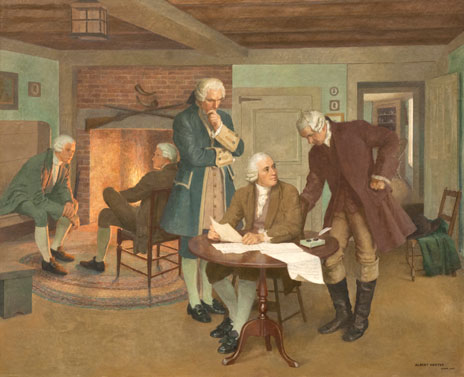

1779: John Adams, Samuel Adams, and James Bowdoin Drafting the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 --Milestones on the Road to Freedom By Albert Herter, 1942 |

“The American Revolution was not a common event. Its effects and consequences have already been awful over a great part of the globe. And when and where are they to cease? But what do we mean by the American Revolution? Do we mean the American war? The Revolution was effected before the war commenced. The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people; a change in their religious sentiments of their duties and obligations.

While the king, and all in authority under him, were believed to govern in justice and mercy, according to the laws and constitution derived to them from the God of nature and transmitted to them by their ancestors, they thought themselves bound to pray for the king and queen and all the royal family, and all in authority under them, as ministers ordained of God for their good; but when they saw those powers renouncing all the principles of authority, and bent upon the destruction of all the securities of their lives, liberties, and properties, they thought it their duty to pray for the continental congress and all the thirteen State congresses. There might be, and there were others who thought less about religion and conscience, but had certain habitual sentiments of allegiance and loyalty derived from their education; but believing allegiance and protection to be reciprocal, when protection was withdrawn, they thought allegiance was dissolved.Another alteration was common to all. The people of America had been educated in an habitual affection for England, as their mother country; and while they thought her a kind and tender parent, (erroneously enough, however, for she never was such a mother,) no affection could be more sincere. But when they found her a cruel beldam, willing like Lady Macbeth, to “dash their brains out,” it is no wonder if their filial affections ceased, and were changed into indignation and horror.This radical change in the principles, opinions, sentiments, and affections of the people, was the real American Revolution.” .............

"... Suddenly, a small door off the stage swung open and in strode Gen. Washington. He asked to speak to the assembled officers, and the stunned Gates had no recourse but to comply with the request. As Washington surveyed the sea of faces before him, he no longer saw respect or deference as in times past, but suspicion, irritation, and even unconcealed anger. To such a hostile crowd, Washington was about to present the most crucial speech of his career.Following his address Washington studied the faces of his audience. He could see that they were still confused, uncertain, not quite appreciating or comprehending what he had tried to impart in his speech. With a sigh, he removed from his pocket a letter and announced it was from a member of Congress, and that he now wished to read it to them. He produced the letter, gazed upon it, manipulated it without speaking. What was wrong, some of the men wondered. Why did he delay? Washington now reached into a pocket and brought out a pair of new reading glasses. Only those nearest to him knew he lately required them, and he had never worn them in public.Then he spoke: "Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I have not only grown gray but almost blind in the service of my country." This simple act and statement by their venerated commander, coupled with remembrances of battles and privations shared together with him, and their sense of shame at their present approach to the threshold of treason, was more effective than the most eloquent oratory. As he read the letter to their unlistening ears, many were in tears from the recollections and emotions which flooded their memories. As Maj. Samuel Shaw, who was present, put it in his journal, " There was something so natural, so unaffected in this appeal as rendered it superior to the most studied oratory. It forced its way to the heart, and you might see sensibility moisten every eye."Finishing, Washington carefully and deliberately folded the letter, took off his glasses, and exited briskly from the hall. Immediately, Knox and others faithful to Washington offered resolutions affirming their appreciation for their commander in chief, and pledging their patriotism and loyalty to the Congress, deploring and regretting those threats and actions which had been uttered and suggested. What support Gates and his group may have enjoyed at the outset of the meeting now completely disintegrated, and the Newburgh conspiracy collapsed." .......

"... And let me conjure you, in the name of our common Country--as you value your own sacred honor—as you respect the rights of humanity, & as you regard the Military & national character of America, to express your utmost horror & detestation of the Man who wishes, under any specious pretences, to overturn the liberties of our Country, & who wickedly attempts to open the flood Gates of Civil discord, & deluge our rising Empire in Blood.

By thus determining--& thus acting, you will pursue the plain & direct Road to the attainment of your wishes. You will defeat the insidious designs of our Enemies, who are compelled to resort from open force to secret Artifice. You will give one more distinguished proof of unexampled patriotism & patient virtue, rising superior to the pressure of the most complicated sufferings; And you will, by the dignity of your Conduct, afford occasion for Posterity to say, when speaking of the glorious example you have exhibited to man kind, "had this day been wanting, the World had never seen the last stage of perfection to which human nature is capable of attaining."

Go: Washington

To the General, Field, & other Officers Assembled at the New Building pursuant to the General Order of the 11th Instant March.

No comments:

Post a Comment